Image credit: Igor Pushkarev. All AdobeStock images in this story are protected by copyright.

Understanding Lead and Fixing Your Drinking Water

My family received a request via a neighborhood app (NextDoor) asking if we wanted our water tested for lead. This got me thinking.

Lead is highly poisonous. For children, the Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention agree that there is no safe blood level of lead.

Lead should not be in drinking water, and can cause a variety of symptoms and illness in children and adults, even at moderate concentrations. The impact of drinking water lead on whole communities has made news headlines around the world.

What is lead?

Lead is a naturally occurring element found in small amounts in the Earth’s crust. While it has some beneficial uses, it can be toxic to humans and animals and cause health effects.

How much lead causes poisoning?

Lead poisoning can occur from small amounts of lead consumed over long periods or from higher amounts of lead over short periods. Lead poisoning is a widespread disease,1 can show terrible symptoms or none at all until it’s too late,2 and has even been implicated in the decline of the Roman Empire.3 Alleviating the health effects of lead can be a long or even impossible process.

Effects of lead poisoning on children and adults

The effects on children’s growth and development can be terrible. An estimated 500,000 U.S. children had lead poisoning in 2017, according to a paper in the peer-reviewed medical journal American Family Physician. A 2020 report in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, estimated 815 million children worldwide have high blood lead levels. The list below of symptoms in children is not intended to catalog all possible health effects from lead; rather it is intended to show you the most significant health effects associated with lead in drinking water:

- abdominal pain

- anemia

- antisocial behavior

- behavioral disorders

- constipation

- convulsions

- high blood pressure

- irritability

- kidney problems

- learning difficulties

- loss of appetite

- low IQ

- poor brain development

- reduced attention span

- reduced educational attainment

- sluggishness or fatigue

- susceptibility to disease

- vomiting

- weight loss

References4 5

In adults lead poisoning can result in:

- abdominal pain

- anemia

- declines in mental function

- headache

- high blood pressure

- kidney problems

- memory loss

- mood disorders

- miscarriage

- muscle and joint pain

- premature birth of babies

- reduced or abnormal sperm

- pain and numbness or tingling in extremities

- skin abnormalities and

- weak muscles

References1 4

Follow my lead

How People Are Exposed to Lead

Lead can enter our bodies through many routes, whether purposefully or accidentally. Lead paint has a sweet taste that can entice children to eat paint chips. Lead can also be accidentally breathed in from contaminated soils, household dust, and when lead-based paint degrades into tiny chips and flakes that can become airborne. The sale and use of lead-based paint was banned in the U.S. in 1978. Lead can also be taken into your body when using some tradition remedies or cosmetics, exposure to battery waste or solder (fusible metal), handling pewter or costume jewelry, use of some pottery and cookware, eating food stored in soldered cans, working in occupations that use lead (e.g., radiology or fetal monitoring), or playing with antique or foreign-made toys.4,6 One of the most insidious and widespread pathways is via domestic water supplies - drinking water.

How Does Lead Get Into Drinking Water?

According to the EPA, “Lead can enter drinking water when plumbing materials that contain lead corrode, especially where the water has high acidity or low mineral content that corrodes pipes and fixtures. The most common source of lead in drinking water are lead pipes, faucets, and fixtures. In homes with lead pipes that connect the home to the water main, also known as service lines, these pipes are typically the most significant source of lead in the water. Lead pipes are more likely to be found in older cities and homes built before 1986. Among homes without lead service lines, the most common problem is with brass or chrome-plated brass faucets and plumbing with lead solder.”

History of Lead in Homes

Lead in drinking water does not normally come from the water source but is added to the water inadvertently during its transport to the point-of-use (POU). Lead was used in United States cities as the main means of piping domestic water supplies until the mid-1900s.

Lead in water is not just a city problem. Lead can be added to water via old lead water mains, from lead service lines coming to a house from main utility supply lines, by lead pipes within an older house, from copper pipe solder joints made prior to about 1986 or using old 50:50 (lead-tin) solder on pipes, from older brass pipe fittings in houses, by new brass pipe fittings that are not certified as lead-free, and from solder joints in hot water heaters.

The most lead can come from main and service lines, but plenty of cases of lead poisoning have been documented due to lead solder and brass in the home. Qualified plumbers will only use lead-free fittings. You should be cautious when ordering plumbing fittings from online sources that may distribute fittings from countries with less stringent standards.

You can tell if your service lines are made of copper, steel, or lead by inspecting where they enter your house. Copper pipes will be copper color, like an old penny. Silver or gray pipes could be steel or lead. If they are lead, you will be able to put a deep scratch in them with a coin. Even if you have no lead pipes entering your house, the main supply lines out under the street may be made of lead unless your area had the utility lines laid under the streets since about 1986. A self-guided tool is available from National Public Radio that shows you how to figure out if your pipes are lead. If you find lead pipes, you may have lead in your drinking water.

If you do not find obvious lead pipes, you still may have lead in your drinking water from the water main, which are the pipes outside the walls of your house or from pipe fittings inside your house. The median age of houses in Minnesota is 43 years. This means that half the houses in Minnesota were built before 1978 and half were built after 1978. And lead-tin solder wasn’t banned for plumbing houses until 1986.

Ages of Houses in Minnesota Counties

Half the houses in Lac qui Parle County were built before 1951, in Yellow Medicine County before 1957, in St. Louis County before 1962, in Ramsey County before 1965, in Lake County before 1970, in Hennepin County before 1972, and in Cook County before 1985. Minnesotans’ chances of having some source of lead in their drinking water are better than 50:50.

Got lead?

If you live in a town with utility lines installed since 1990 in a new house built since 1990 with all plastic pipe, you likely have no large source of lead in your drinking water systems. If your town or house are older, it is hard to guess. Because the presence of lead affects our families’ health, knowing whether your home has lead is definitely much better than guessing. Luckily, there are easy ways to have your water tested.

Lead Testing

It is pretty difficult to perform a reliable test for lead in water because concentrations of concern are in the 10 parts per billion range (think 1 penny out of $1 million) and lead exists as dissolved lead and as particles in your water. The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) checks out the quality and accuracy of lead tests done by laboratories in Minnesota and keeps a list of accredited water testing laboratories (also see this link to lookup laboratories). To be reliable, these tests are done by qualified personnel who have done hundreds of tests with expensive equipment and clean, appropriately equipped laboratories. To make sure the results are reliable, these laboratories do extensive quality assurance and quality control and have to pass regular certification testing by state or federal organizations.

Testing Laboratories

The table below lists the MDH-certified laboratories in Minnesota who were offering drinking water lead testing for residential customers in September 2021 and who would answer my phone calls or emails with clear information. There may be other businesses offering lead testing but if you find one, make sure that they are certified by MDH to do drinking water lead testing. The listing of laboratories below does not imply endorsement or recommendation by myself or Minnesota Sea Grant. Table updated 5/18/23.

|

Laboratory |

Location |

Telephone |

Cost |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brainerd, MN |

218-829-7974 |

$32 |

$32 plus $7 shipping fee |

|

|

Fridley, MN |

763-571-3698 |

$50 |

Bottle can be either mailed out or picked up at office; |

|

|

Circle Pines, MN |

763-786-6020 |

$100 |

Pick up kit from them because they are preserved with nitric acid (they do not ship) |

|

|

St. Paul, MN |

651-642-1150 |

$75 |

Pick up containers or they are shipped at a nominal charge |

|

|

New Ulm, MN |

800-782-3557 |

$21 |

Lab supplies bottles |

|

|

Minneapolis, MN and other locations |

612-607-1700; |

$275 |

Do not do individual lead tests but do a full metals panel for $275 |

|

|

Bloomington, MN; Detroit Lakes, MN; Hibbing, MN |

952-456-8470; 218-846-1465; 218-440-2043 |

$25 |

Requires company-supplied sampling container |

|

|

Southeastern Minnesota Water Analysis Laboratory (Omstead County) |

Rochester, MN |

507-328-7495 |

$28 |

Pick up materials in Rochester, MN |

|

St. Joseph, MN |

320-251-5090 |

$45 |

Company responded with sampling procedure pdf and price quotation |

|

|

Hopkins, MN |

952-935-3556 |

$75 |

Supplies sample bottles and instructions |

|

|

Janesville, MN |

507-234-5835 |

$65 |

Lab supplies bottles and instructions; two week turnaround |

|

|

Elk River, MN |

763-441-7509 |

$50 |

Company supplies sample bottle and instructions |

|

| EMSL Analytical, Inc. | Minneapolis, MN | 763-449-4922 | $100 | One week turnaround |

Testing Process

Generally, the process for testing for lead is quite simple and easy. You pick up sampling bottles from the laboratory or the laboratory mails them to you with instructions for how to take a water sample.

Sampling is meant to represent the worst case, so it is important to take samples from a faucet that has been undisturbed for as long as possible (e.g., overnight). If you sample from a tap or faucet that has been allowed to run, any possible lead may be reduced by being flushed out.

The sample bottle is then sealed and sent or taken back to the laboratory for analysis. Generally, results are sent back to the customer in a few days with information about how to interpret the analysis. In the past, the lead level mandated by the EPA that would compel a community water system to take action to reduce lead levels was 15 parts-per-billion (0.015 milligrams per liter or mg/L). Recently, this trigger level has been revised down to 10 parts-per-million (0.01 milligrams per liter or mg/L) with the caveat that there is no safe level for lead in drinking water.

What about do-it-yourself (DIY) testing? If you shop online, you will find many home testing kits for lead in drinking water. The advertisements will say things like, “verified accurate by an EPA-approved method,” “tested by a team of EPA experts,” or “with EPA or WHO record of standards.” Because lead is a powerful poison, I suggest doing yourself and your family the favor of having a certified laboratory do the analysis.

Let’s Get the Lead Out!

If you find lead in your drinking water supply, the ultimate means of fixing it is replacement of all lead-containing pipes and fittings in your home, the service line, and the water main. The water main is the responsibility of the utility supplying the water but the part of the service line coming into the house across the homeowner’s property is usually the responsibility of the homeowner. All plumbing and fixtures in the home are, of course, the responsibility of the owner. Replacement of water mains and lines that belong to a utility is an expensive and long-term job, requiring substantial investment of tax monies that is unlikely to be solved in the short-term. Replacement of the owner’s service line is also expensive and requires digging out the old pipes and replacing the pipes under the owner’s property. This is also expensive and takes hiring a licensed contractor. Replacement of pipes, water heaters, and fittings inside the house that are connected to drinking water supplies is best done by a licensed plumber. Some small jobs can be DIY, especially the installation of PEX (cross-linked polyethylene) pipes and fittings (there is no lead in PEX tubing). All fittings should be certified lead-free by appropriate certification organizations. The EPA supplies a quick guide for identifying appropriate certification marks for fittings connected to drinking water supplies.

What Can You Do?

Below are some lead-removal options.

Bottles. You can buy commercially bottled water, but bottled water costs an average of 2000-times more than tap water and 1000-times more than water treated by in-home filtration.

Renovation. Removal of all lead from your water supply is the best way to avoid lead exposure, but that can be expensive and time consuming.

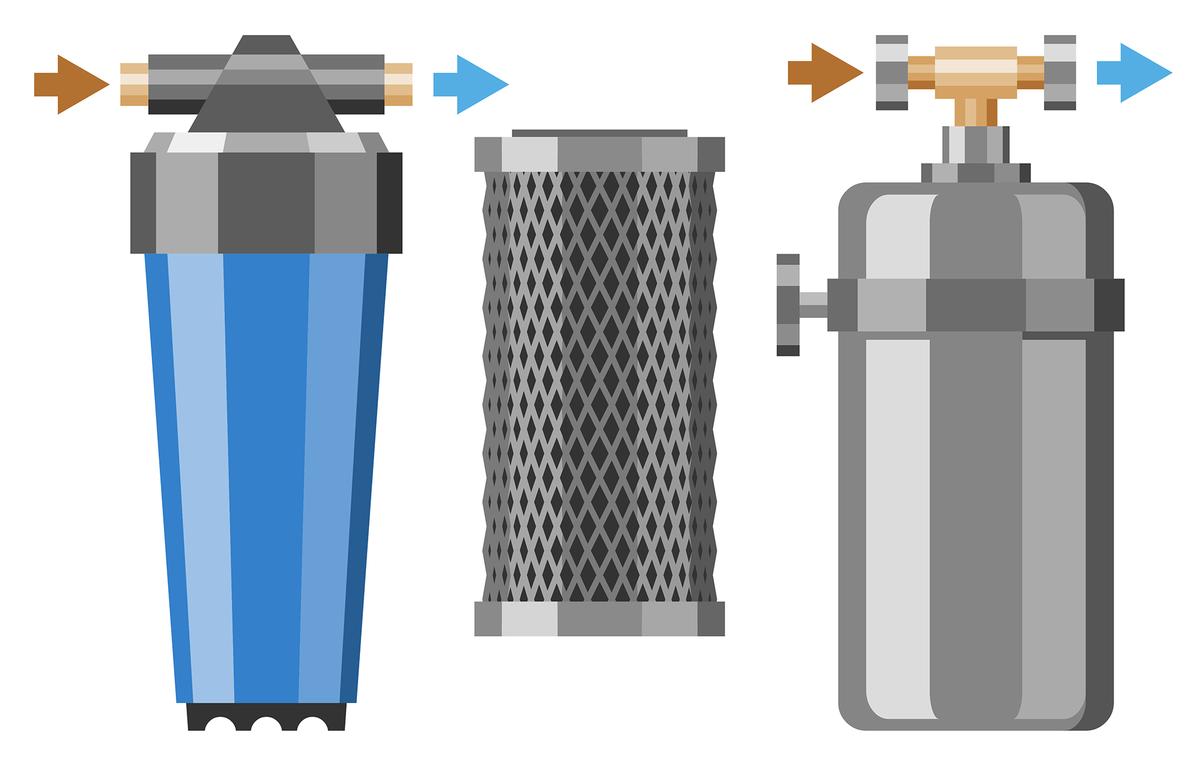

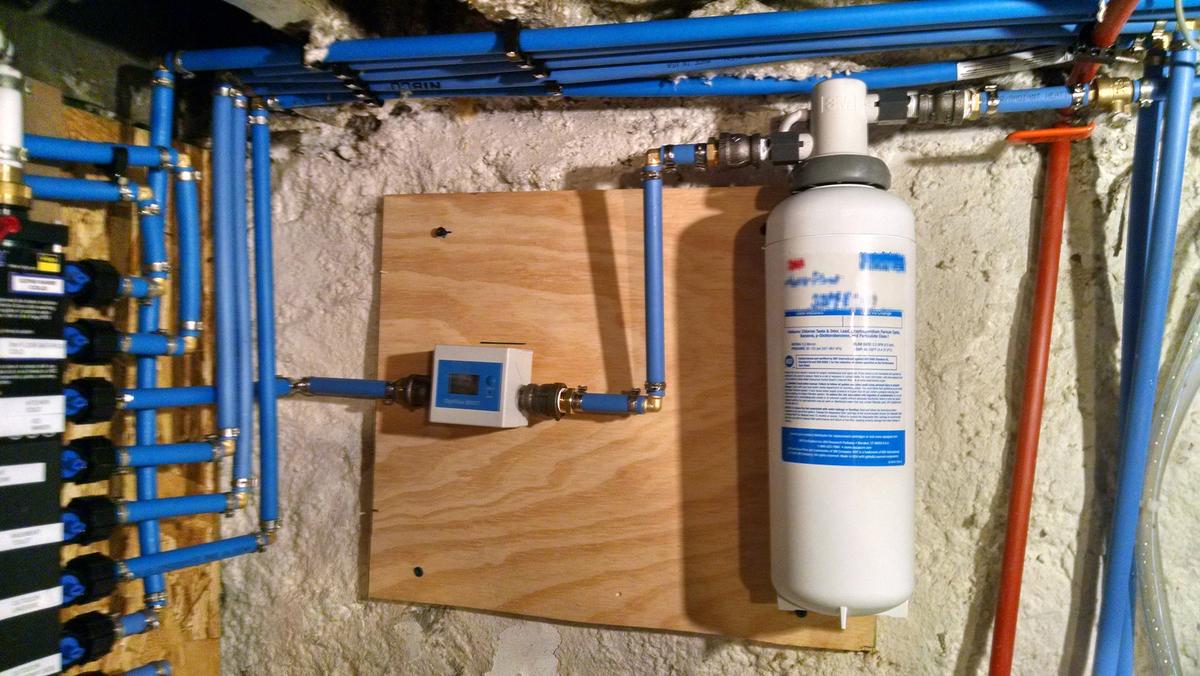

Filters. Several technologies are available to mitigate lead in drinking water.

- Point-of-entry (POE or whole-house). POE treatment for lead is rare and extremely costly so I do not address it here.

- Point-of-use (POU, often under sink or faucet mounted) and water purifying pitchers. Two things are important when purchasing/installing, and operating a lead filter. First, because lead moves as particles and dissolved material,7 all mitigation equipment and fittings should meet NSF-ANSI standards 53 (for dissolved lead and other potentially harmful materials8) and 42 (for small particles and esthetic issues). Second, because filtration and mitigation supplies become clogged and ineffective as they are used, you need to follow manufacturers’ specifications for operation and replacement of filter media.

How to Select a Water Filter – What are NSF/ANSI Standards?

The National Sanitation Foundation (NSF) and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) are testing standards that are meant to help keep consumers safe by ensuring the efficacy of manufactured goods. NSF is a nonprofit organization that develops public health standards and certification programs that help protect the world’s food, water, consumer products and environment. ANSI is a nonprofit whose role is promoting and facilitating voluntary consensus standards and conformity assessment systems, and safeguarding their integrity. ANSI and NSF collaborate on establishing and coordinating public health, safety and environmental standards.

Standard 53 and Standard 42

If you’re not familiar with the details of NSF-ANSI standard 53, you’re not alone! It cost me $165 and two hours disentangling the security protections on ANSI’s website to be able to look at standard 53. It is surprising to me that something as important to the American consumer as a health-sustaining set of public standards would be locked behind a nonprofit’s paywall. With all the talk in the government about ensuring open access to scientific information this seems like an anachronism, especially because federal agencies recommend purchasing only equipment following these standards.

NSF-ANSI Standard 53

This standard is the most important of the two standards (53 and 42) because it sets standards for removal of materials of health concern. This standard requires that each filtration system be “challenged” by running it using a high-lead water source that is similar to the kind of tap water and at use rates found in homes. The test water is spiked with about 150 ppm of soluble lead and the filter must reduce this to a maximum outflow concentration of 5 ppm. This represents about a 97% reduction, at minimum. But remember, there is no safe amount of lead in drinking water.

Because particles of lead will be more common in water with a high pH (8.5 or pretty high pH for domestic water), particulate filters must also be tested to make sure they remove lead particles down to 0.1 micron is size (smaller than most bacteria; about one-thousandth the thickness of a piece of paper). The tests are run many times and in on-off cycles that simulate water use found in homes and at temperatures that are close to room temperature.

Tests like this are run on all types of filters including POE, POU, pitchers, drinking water bottles and refrigerator filters. For plumbed-in systems, the flow rate through the filter must not decrease by more than 25% by the end of the rated gallon capacity or it cannot claim attaining this standard. Therefore, all water filters qualifying for standard 53 will remove at least 97% of the lead in water. These filters will also remove a lot of other unwanted materials, including particles, chlorine, bad flavor, other metals (like arsenic and others), disease-causing organisms, some organic chemicals, and other stuff you’d like to avoid.

How to Choose In-Home Lead Treatment Methods and Equipment

Choosing the right way to remove lead in your home requires you decide a few things.

First, where in your house do you want to be able to draw lead-free water. If it can conveniently be at a single faucet (e.g., in your kitchen) this simplifies matters and reduces treatment costs.

Second, how much water do you want to filter? This is important because all water filtration systems are manufactured with a specific filtration capacity and the systems stop working until a new filter cartridge is installed. To determine the flow rate of the faucet or faucets you want to use for drinking water use the stopwatch function on your smartphone to measure how long it takes you to fill a one-gallon container. This should be done while no other water in the house is running.

Here’s the math:

- Take 60 (seconds) and divide that by the number of seconds it took you to fill the one-gallon container.

- Example: In my house, it took me 65 seconds to fill a one-gallon jug, so my maximum flow rate is 60/65 or 0.92 gallons per minute (GPM).

- Now think about how long during a typical day you run that cold-water faucet.

- Example: If I run my cold water 20 minutes per day, I am drawing about (0.92 GPM) x (30 days) x (20 minutes per day) or 552 gallons per month or over 6,600 gallons per year.

This simple math will help you to calculate the cost and the bother of buying and installing filter cartridges when you choose a filter system

The next step is to check the list of manufacturers offering filter systems that satisfy NSF standard 53 (see the NSF list of POU systems here). These include plumbed-in systems working with a separate faucet or the existing plumbing, those mounting on faucets, counter-top units connected to faucets, pitcher or carafe filters, and the more complex reverse osmosis systems. The list is quite extensive so may take some time to page through. It treats all types of filters. Some of the companies will likely be familiar to you but others may not be. Most list the volume of water that can be treated with each filter. You can use this as a guide for looking up the costs of replacement filters online or elsewhere so you can judge availability and cost.

Costs. Dividing the cost-per-filter by the volume listed will tell you how much lead removal will cost per volume. The filter for my under-sink unit costs about $165 but it treats 6,000 gallons safely. A pitcher unit I have has a much cheaper filter ($9) but only treats 40 gallons before replacement. The under-sink unit costs less thanone-tenth than the pitcher filter to operate.

Make sure that whatever you buy, you can get or request the NSF Performance Data Sheet for your model prior to purchase. This will show you the results of various tests and how well the product met the standards. For lead and for other contaminants, it will normally tell you the influent (water flowing into the unit) concentration, the average rate of reduction (often as a percentage), and the permissible concentration in the effluent water (water flowing out of the unit). Asking for the Performance Data Sheet is part of being an informed and responsible consumer.

No matter what kind of NSF standard 53 certified water filter you use, it will not work if you don’t follow manufacturer’s instructions. These are more than recommendations. They are the conditions under which the filter met test requirements. If you fail to follow the instructions, lead may not be removed. Some of the specifications concern acceptable water temperature and pressure, the maximum flow rate (set at 2.5 gallons per minute by standard 53), and the maximum number of gallons that can be effectively passed through the filter. Pitcher filters are particularly difficult to monitor because indicator lights usually just count out a period of time, not the amount of water filtered. Although some plumbed-in filters use a system that shuts off water when a maximum number of gallons have been filtered, I added a $30 digital meter to mine, available from online retailers, that tells me when enough water has passed through the filter to exhaust it.

A recent test of POU filters10 shows that there are several things that can make even certified filters fail. Among the most important factors is whether the lead is dissolved in the water or suspended as particles. In places that have experienced very high lead levels (i.e., >1000 ppb; e.g., Flint, Michigan11 and Newark, New Jersey12), more of the lead was moving as particles than in the ANSI-NSF challenges (tests) of standard 53. POU filters do not do as well filtering particles as they do at filtering dissolved lead. Some of these lead-containing particles are extremely tiny meaning that choosing filters removing particles of 0.2 micron or less particles would be desirable and would work better. Other challenges with POU devices have included very slow filtration and flow rates, leaks and physical failure, inconsistent functioning among duplicate devices, and manufacturing flaws.

If you live in a house with lots of old iron pipes or your neighborhood is older, it is a good precaution to add a simple particle filter ($20-$50) between your water entry and your lead filter system. If your house’s water or the neighborhood’s water gets turned off for maintenance and then turned back on again, there’s a good chance a lot of rust particles will get into your water supply. These relatively inexpensive particulate filters can catch the rust and lead bits before they get to your more expensive lead filter. If you don’t have or install a particle filter and your water gets turned off, make sure that you run all of the rust out of the system at another sink that does not have a lead filter before you run any water through the lead filter.

It is important to underscore that all certified lead filters remove substantial lead from drinking water. They work better at moderate to low levels of lead (e.g., less than 150 ppm), in situations where most lead is soluble, and when operated within the operating specifications of the manufacturers. One way to find out whether your filtration system is working right is to test the water after it has passed through the filter, using one of the laboratories listed above.

Take the Lead (le e

e d) on Lead (lɛd)

d) on Lead (lɛd)

Protecting our families and especially our children from lead in our drinking water can be costly. It can cost between $18 and $250 to test household water for lead. It can cost more than $1,000 to replace the main service line to a house. It can cost $30 to $1,000 or more to install filtration or reverse-osmosis equipment to remove lead. It can cost $14 to $300 or more to regularly change lead water filters.

Much of these remediations may be economically inaccessible to us and to many of our neighbors. In ancient Rome, it was the wealthy who suffered the effects of lead poisoning from their water because they were the only ones who had (lead) plumbing.3 In contrast, today it is disadvantaged neighborhoods who are disproportionately impacted by drinking water lead concentrations due to economic disparities, lack of access to services and infrastructure improvements, and other inequities.13 If you can afford to test and treat your water, please consider assisting a neighbor or community members who are not as fortunate. By helping each other, we can make our water world safer for everyone.

Bibliography

1 Barltrop, D. in Poisoning Diagnosis and Treatment (eds J. A. Vale & T. J. Meredith) 178-185 (Springer Netherlands, 1981).

2 Waldron, H. A. Subclinical lead poisoning: a preventable disease. Preventive Medicine 4, 135-153 (1975).

3 Needleman, L. & Needleman, D. Lead Poisoning and the Decline of the Roman Aristocracy. Echos du monde classique: Classical views 24, 63-94 (1985).

4 Bhowmik, D., Kumar, K. P. S. & Umadevi, M. Lead Poisoning- The Future of Lead’s Impact Alarming on Our Society. Pharma Innovation 1, 40-49 (2012).

5 WHO. Lead poisoning and health, <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health> (2019).

6 Debnath, B., Singh, W. & Manna, K. Sources and toxicological effects of lead on human health. Indian Journal of Medical Specialities 10, 66-71, doi:10.4103/injms.Injms_30_18 (2019).

7 Doré, E. et al. Effectiveness of point-of-use and pitcher filters at removing lead phosphate nanoparticles from drinking water. Water Research 201, 117285, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.117285 (2021).

8 NSF International. 164 (NSF International, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 2019).

9 Kim, E. J., Herrera, J. E., Huggins, D., Braam, J. & Koshowski, S. Effect of pH on the concentrations of lead and trace contaminants in drinking water: A combined batch, pipe loop and sentinel home study. Water Research 45, 2763-2774, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.02.023 (2011).

10 Purchase, J. M., Rouillier, R., Pieper, K. J. & Edwards, M. Understanding Failure Modes of NSF/ANSI 53 Lead-Certified Point-of-Use Pitcher and Faucet Filters. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 8, 155-160, doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00709 (2021).

11 Bosscher, V., Lytle, D. A., Schock, M. R., Porter, A. & Del Toral, M. POU water filters effectively reduce lead in drinking water: a demonstration field study in flint, Michigan. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 54, 484-493, doi:10.1080/10934529.2019.1611141 (2019).

12 Lytle, D. A. et al. Lead Particle Size Fractionation and Identification in Newark, New Jersey’s Drinking Water. Environmental Science & Technology 54, 13672-13679, doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c03797 (2020).

13 Hanna-Attisha, M., LaChance, J., Sadler, R. C. & Champney Schnepp, A. Elevated Blood Lead Levels in Children Associated With the Flint Drinking Water Crisis: A Spatial Analysis of Risk and Public Health Response. American Journal of Public Health 106, 283-290, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.303003 (2015).

Resources mentioned in this story

- EPA CDC: Basic Information About Lead and Drinking Water

- Mayo Clinic: Lead Poisoning

- A Very Brief History of Lead in Water Supplies

- When Lead Went Dead

- NPR: Find Lead Pipes in Your Home

- American Housing Survey

- Median Age of Homes in the United States

- Accredited Labs in Minnesota Accepting Samples from Private Well Owners

- Search for Accredited Laboratories (Minnesota Department of Health)

- EPA Proposes Updates to Lead and Copper Rule to Better Protect Children and At-Risk Communities

- Cost of Bottled Water: Why is it so Expensive?

- Are Plastic Water Filter Pitchers OK to Use?

- National Sanitation Foundation

- American National Standards Institute

- EPA: Consumer Tool for Identifying Point of Use (POU) Drinking Water Filters Certified to Reduce Lead

- How to Identify Lead-Free Certification Marks for Drinking Water System and Plumbing Products